The Coldest Mountain

Author

Brandi Hammon

Published

May 11, 2023

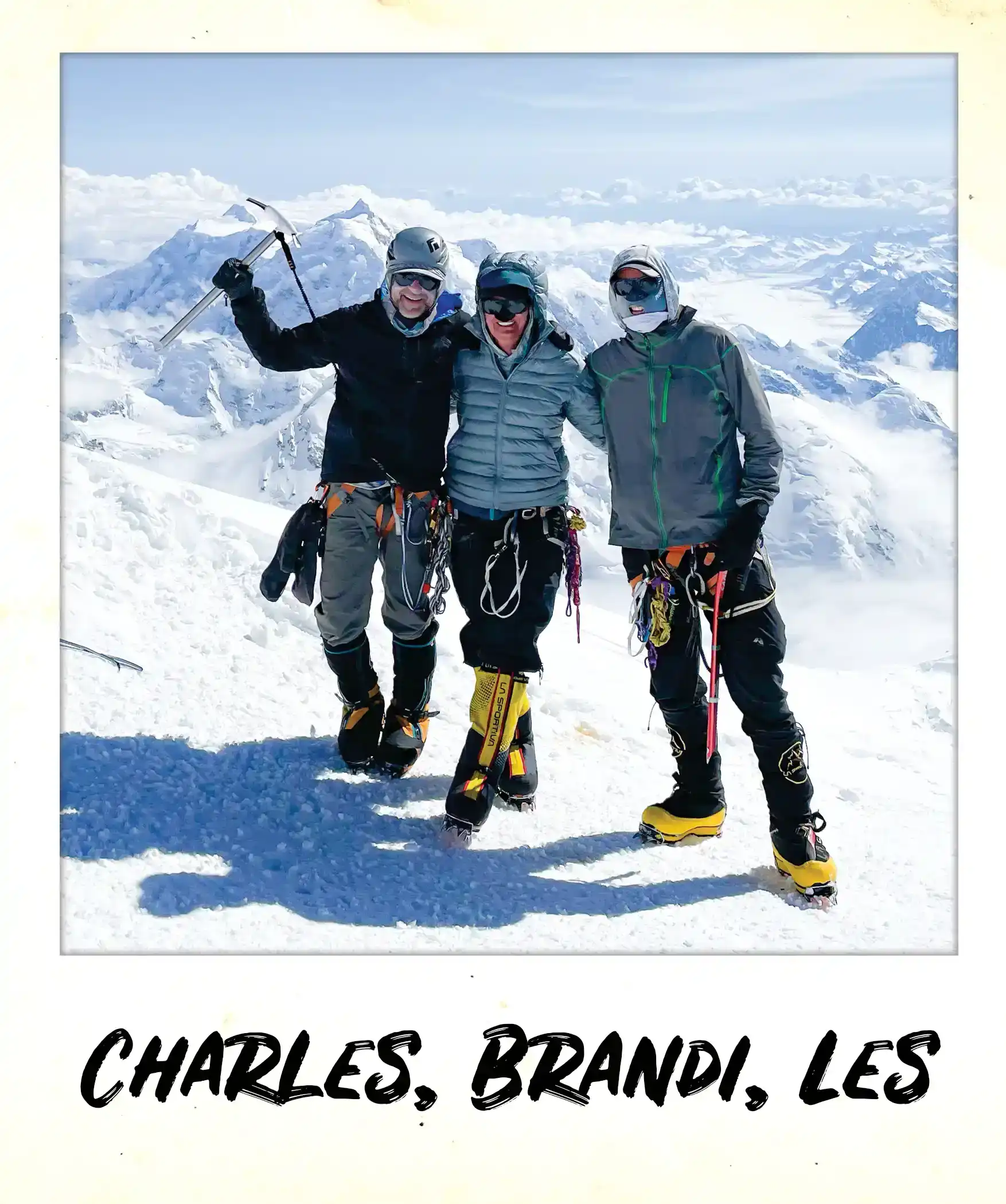

An Out of Bounds Adventure on Denali

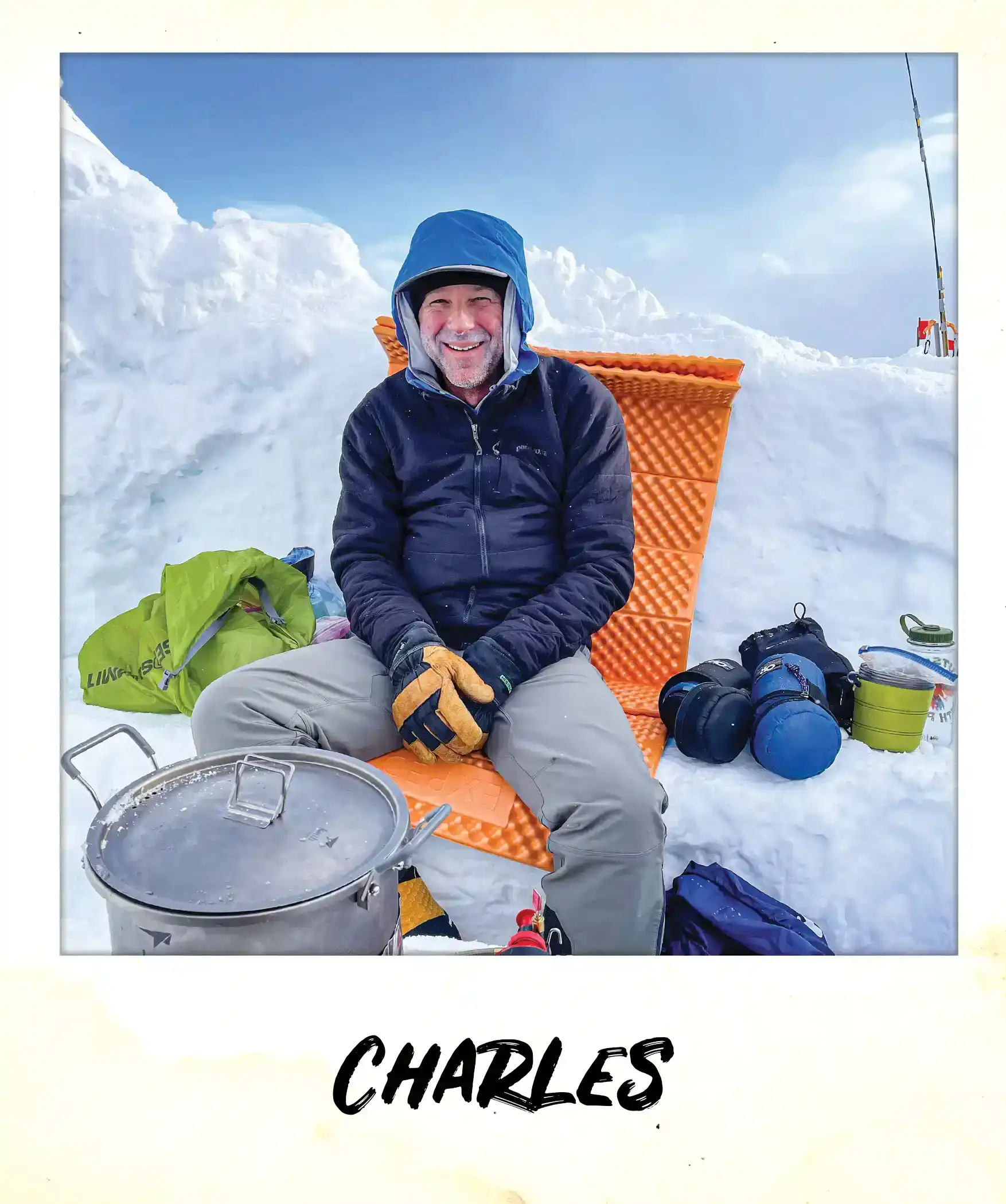

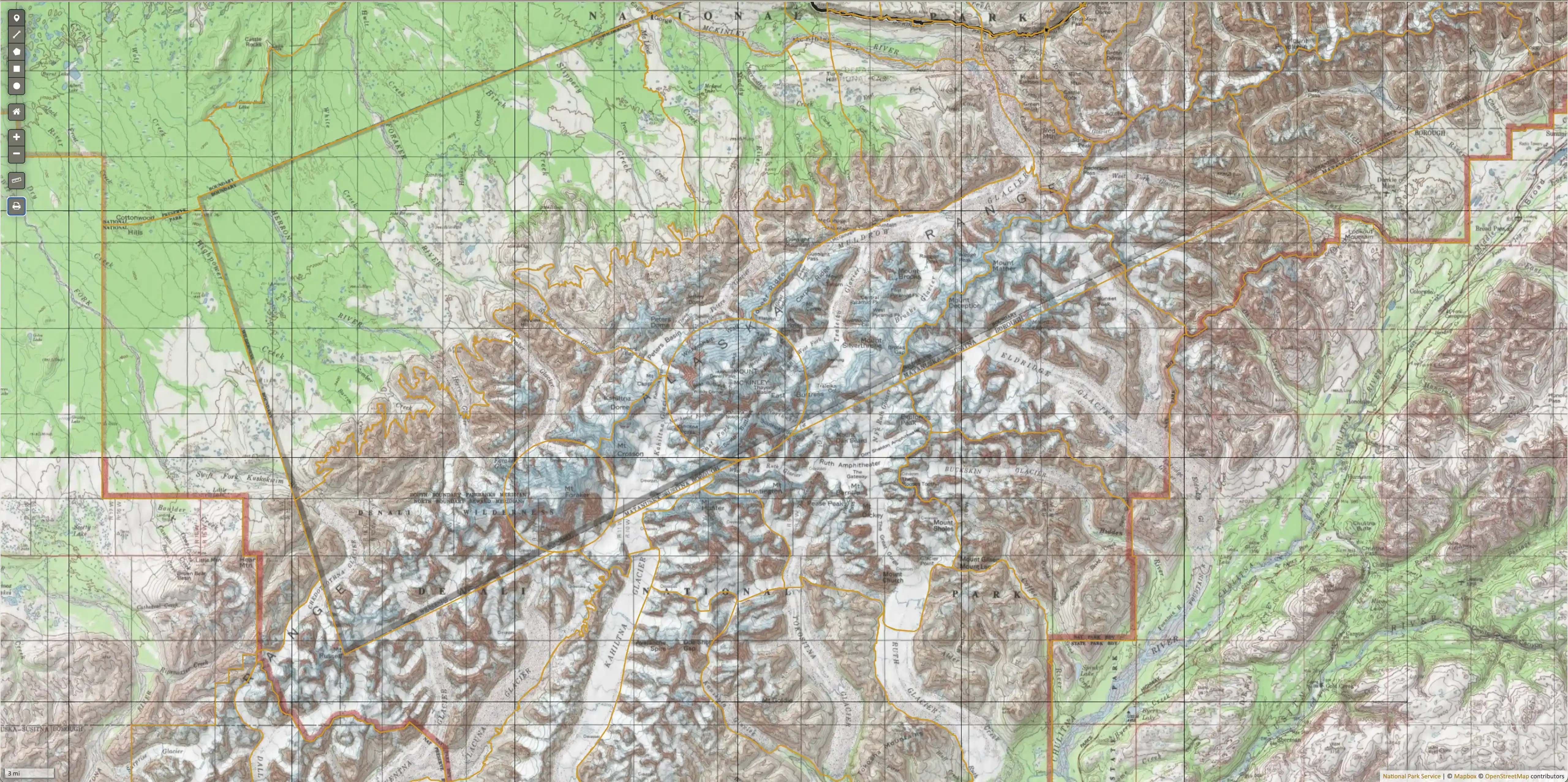

Denali has evaded me over the past 20 years; pregnancy, bailing climbing partners and finally, Covid in 2020 felt like the universe just didn’t want it to happen. In 2021, it didn’t feel much different; with three months of construction delays, the grand opening of Mountain Luxury’s new office pushed to May 22nd, a last minute root canal on May 25th, and my middle son graduating high school May 27th, all had tested my capacity as a human. With hair on fire, the morning of May 28th, Les, Charles (my college climbing buddy), and I jumped on a plane bound for Anchorage, Alaska to climb North America’s tallest and most beautiful mountain, Denali.

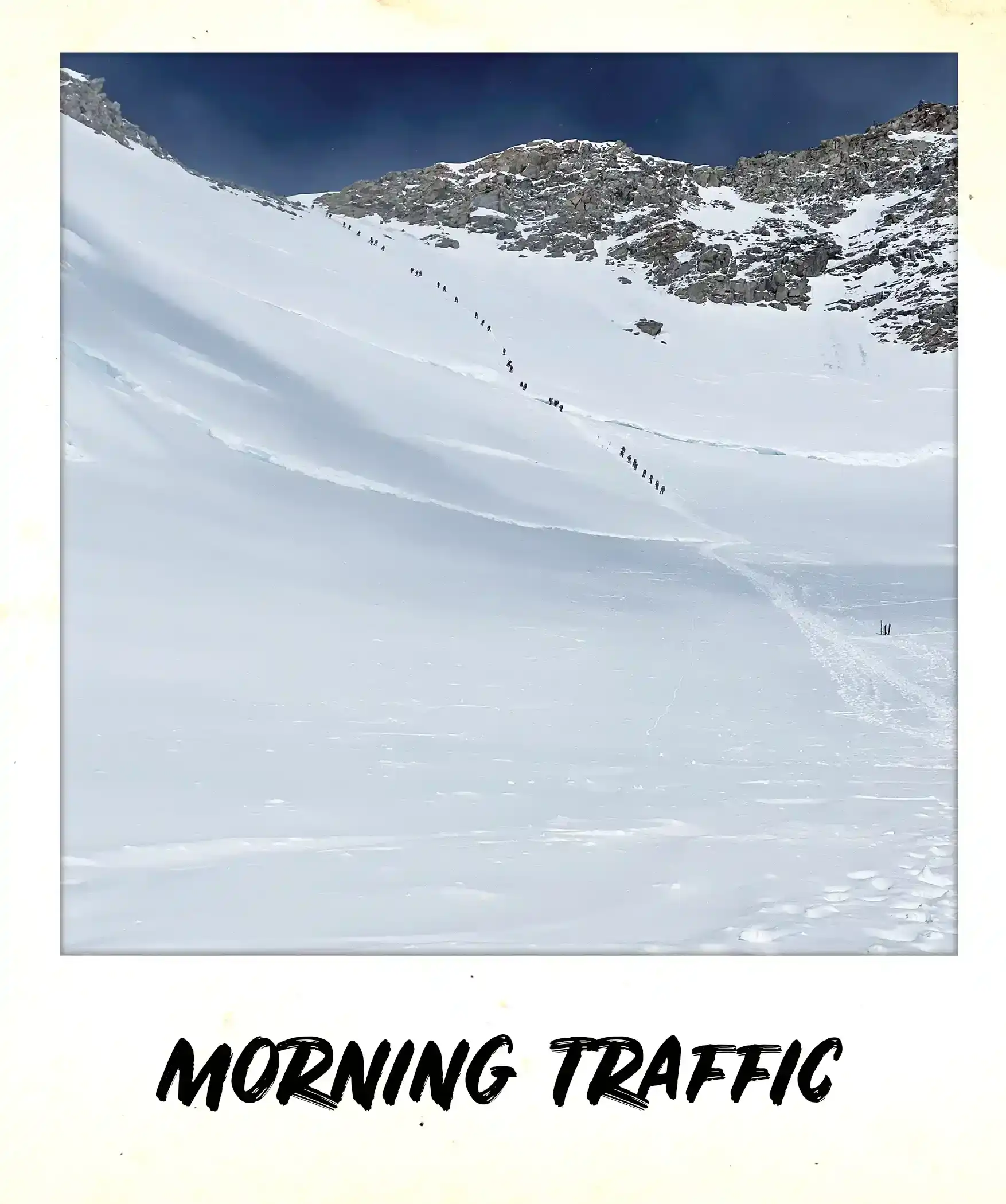

An average of 1,100 climbers head to the mountain over the course of 8 weeks to make their ascent. Of them, half or less make it to the top. Denali is a grueling mountain; the air is thinner making a summit on Denali at 20,310 feet feel more like 24,000 feet in the Himalayas. Climbers don’t use supplemental oxygen or porters, who carry substantial loads of gear, prepare food, set up camp, and melt water. The Google search result for the world’s coldest mountain is Denali. It is a beast, North America’s highest summit, an amazing adventure, and a test of the human spirit. It also has risks. Prior to departing, I wrote a letter to my three children hoping they would never read it.

Food

The physical demands of mountaineering are extreme. The entire expedition’s meals are weighed, packaged into baggies to save weight and marked with caloric value. The ratio of weight to calories of food impacts the menu and for the record, chocolate covered cinnamon bears are the highest calorie dense food by weight. One day’s food weighs 2 pounds multiplied by 24 days and the pack is now 48 pounds heavier. Ever grab a 50 pound bag of cement and thought, “I should carry that around for 3 weeks?” Me neither.

Logistics

Preparations begin in the year before attempting Denali. Les, my husband, has summited Denali twice; once with a guided group and again on the Muldrow Glacier route with friends. Since I work a lot and abhor the minutiae of planning, he handled 90% of it. We have been together for over 20 years now, and when I look back and think about why I married him, I swear this must have crossed my mind. He can handle the most tedious tasks like organizing 144 meals, deconstructing the mechanics of a sled and how to stabilize it, how to rebuild a camp stove on the mountain and build the perfect cook tent at altitude and on it goes. He buys our gear, organizes adventures, and gets us out the door. It makes for a great match. I do remember, early on, he bought me a headlamp and climbing helmet as a gift and I was in love.

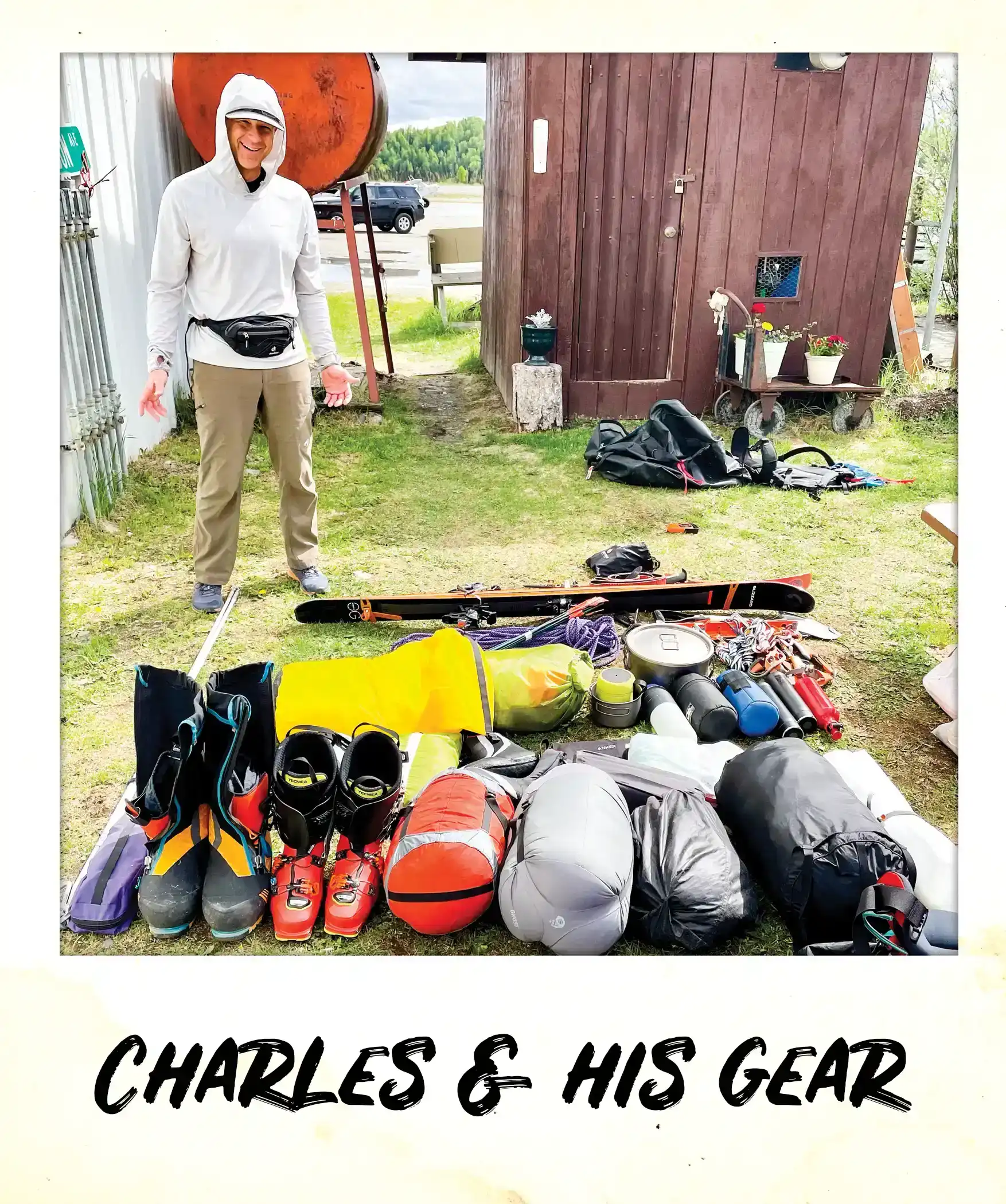

Plan for the worst, and hope for the best. Conditions on Denali lead to a plethora of things that may go wrong due to the length of time, cold temps, and high altitude. Risks fall into a few categories; accidents in every imaginable form; physical including sickness, injury, and fitness; weather may lock teams down for 10 days, snow, wind, sunburns, and freezing temps; mechanical issues ranging from packs to tents, boots, gear, or stoves that don't work can end a trip or worse. The logistics of this climb involve making every attempt to overcome those risks without adding too much weight. Unfortunately, there are too many to plan for but every item is carefully considered before it is packed.

Let’s Go!

All of Denali’s shenanigans begin in Talkeetna, Alaska. The town is worth the visit. To mountaineers, it is full of hope, folklore, and kind enough to drown even the most wrecked egos. Alaskans are a tough bunch handling extreme conditions but are also bonded to other humans. They see you, hold the door for you, share a passing smile but don’t fret over you.

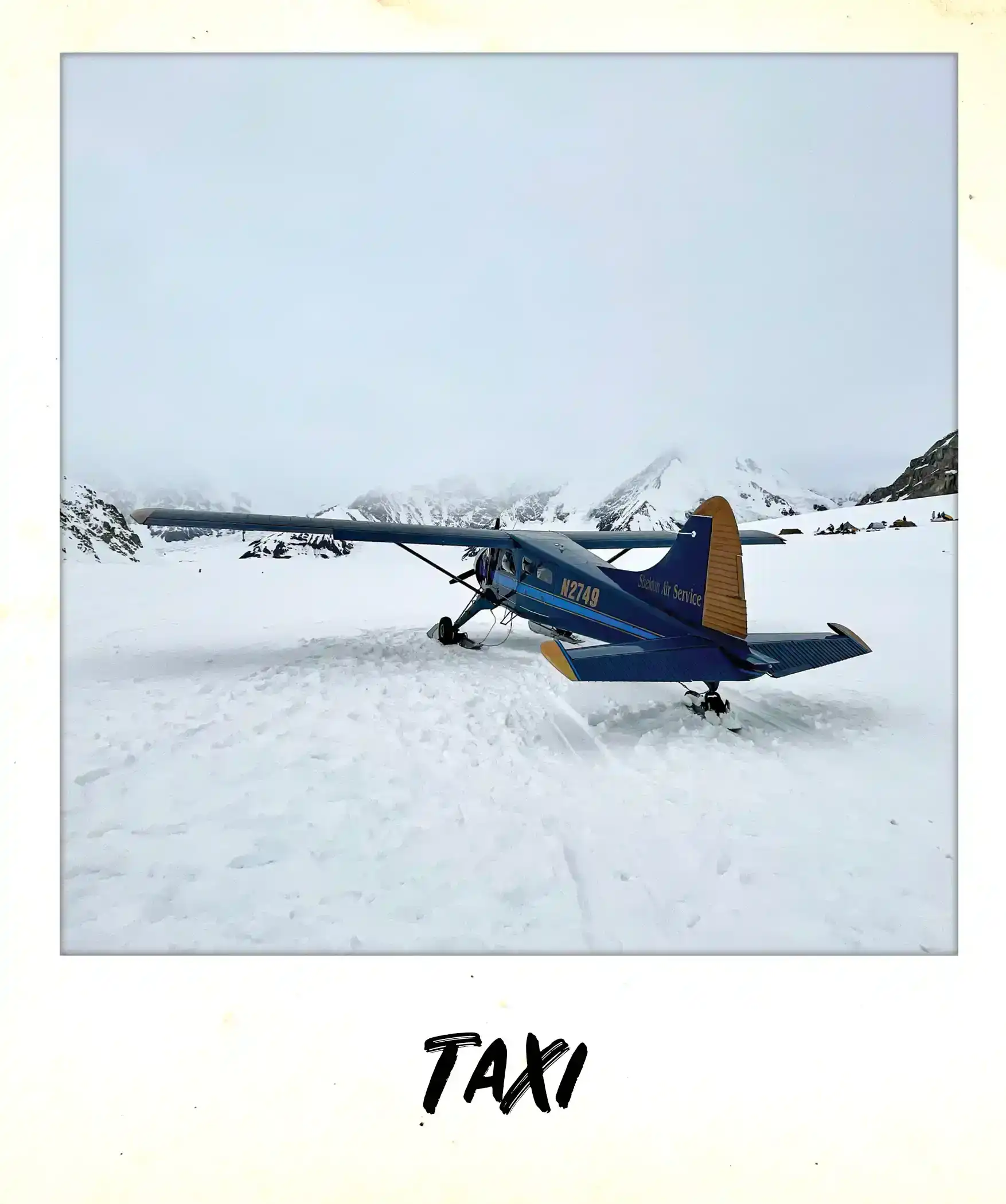

Our taxi out of Talkeetna to Basecamp was on Sheldon Air. It is a familiar hanger that feels (and smells) like grandma’s house. Before loading the planes all food and gear is weighed. I was mortified when ours weighed 137 pounds each and Charles’s weighed 168. OMG, I don’t think I trained for that!

The flight into Basecamp was a transition as green became white, the rivers became glaciers, and everything morphed into shades of black and white except the blue sky and ice. The engine humming overtakes your mind as the pilot ascends over the changing lands below.

Basecamp was rife with anticipation, the burbs of the Alaskan range. Full of hope, excitement, cockiness and honestly, a bunch of folks with no idea of what lay ahead. The stoke at just being there was palpable as the icefall echoed down to the valley under Mount Hunter. Through the colorful tents I caught the glimpse of another female climber, always an exciting moment for me. As I looked closer she had a prosthetic leg, upping her badass status.

We had a leisurely start but eventually we skied, hauling our 140 pounds to Camp 1. It was surreal as we were all smiles saying, “hi” to every cracked lip, sunburned, deflated soul snowshoeing down that mountain. They were on a death march as we passed each other. Me, heading up into the unknown, smiling oblivious to what lay ahead; them, wanting nothing more than to get back to Basecamp and fly off the mountain in search of a burger and beer. The contrast wasn’t lost on me, it was foretelling of the struggle that lay ahead.

We skied 1000’ over 5 miles, a cruiser kind of day. Past Mount Foraker and over the beautiful Kahiltna glacier, simply stunning and I was in awe the entire day. Before falling asleep under the glacier, I messaged my team at home to ensure all was well with the company and ease their nerves.

Camp 1 to Camp 2

7,800' – 11,200'

It snowed that first day and I read through an entire book. Camp 1 was full of bravado, the human spirit intact as climbers excitedly told their stories, showing off gear and ingenious systems. Camp is set up on prior campsites to save time from building new snow walls, cook tent sites and “bathrooms”. Holes from those camps loom under fresh snow and can drop you 12 inches making your teeth jar.

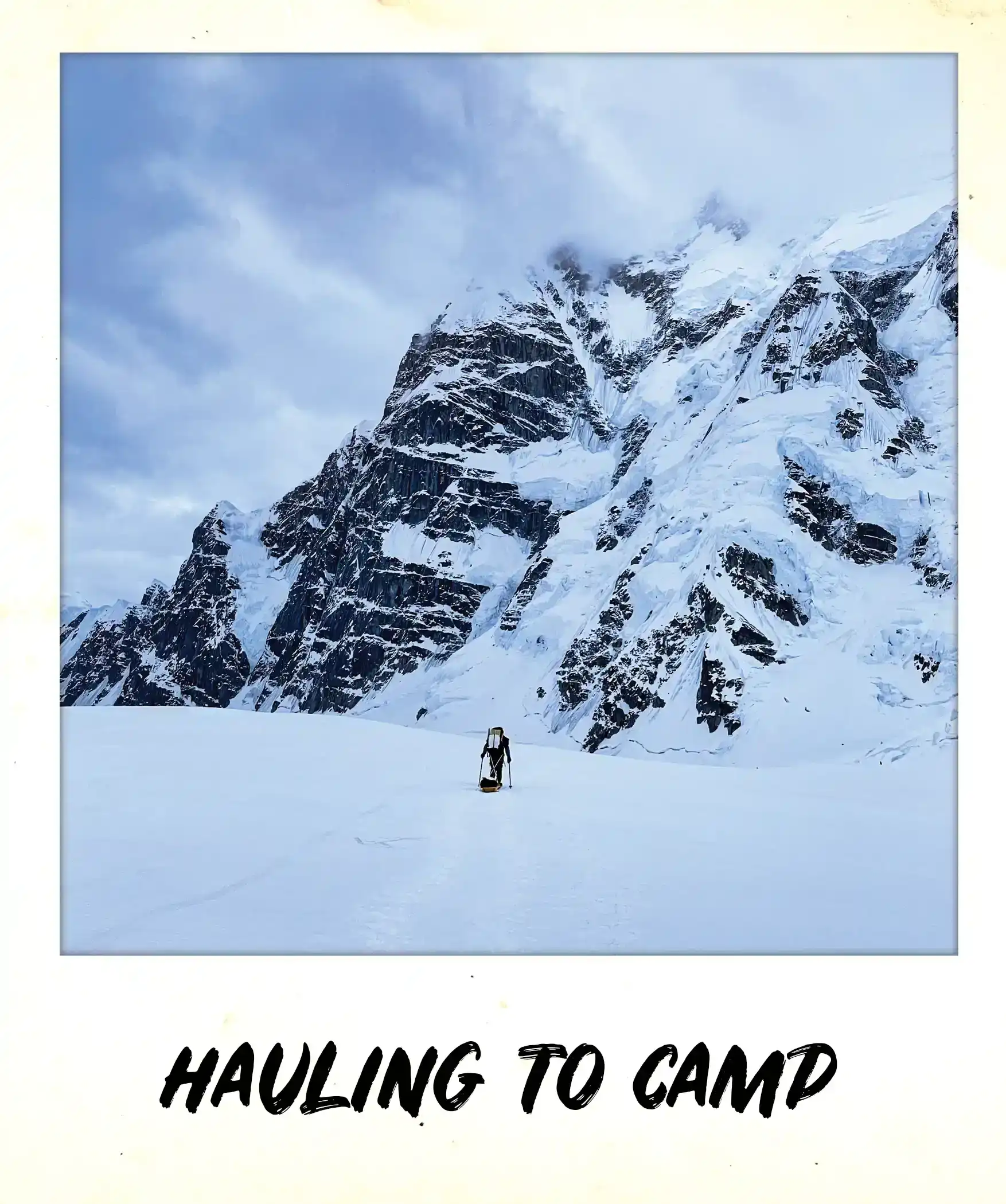

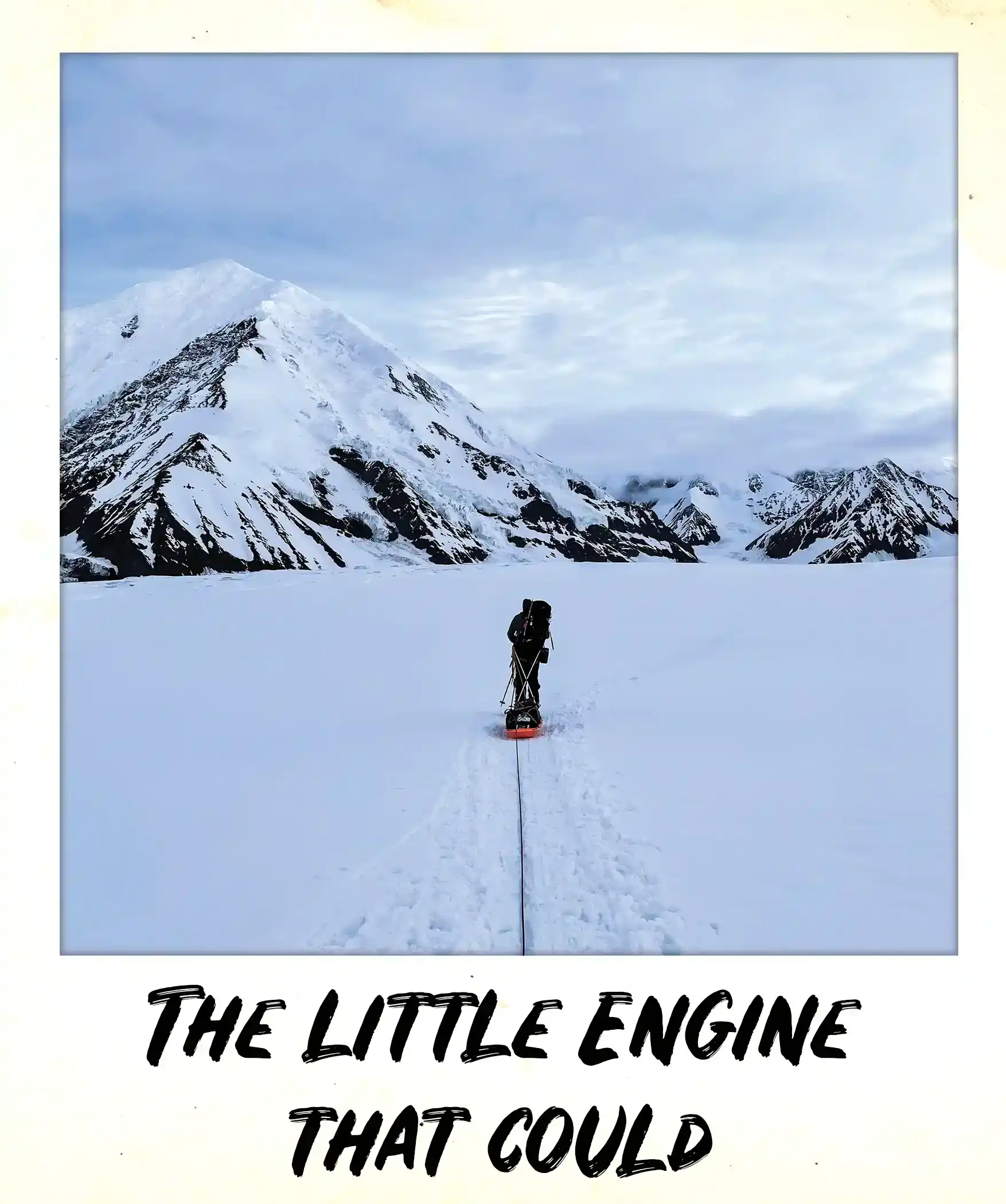

Waking the next day to fresh snow and blue skies meant we were moving on up. We packed up all the food for our climb ahead and other items unnecessary at camp 1 and proceeded to carry them halfway to Camp 2. WHAT?! This logistical maneuver was something I was not aware of. Loads are excruciatingly heavy, the steeper it is the less weight should be on the sled and moves into your pack. With 140 pounds each, we needed to shuttle our stuff. That meant we hauled half the weight about halfway up, buried it and came back down to camp. And it meant, we climbed most of the mountain twice. At least it meant more ski turns down in fresh powder.

The next day we broke down camp 1 and skinned to camp 2 at 11,200 feet. As we passed the buried cache I smiled, proud of the work done to get it there. It was a long hot sweaty day, trying to stay cool but not expose any skin as the sun was reflecting off the snow like a parabolic mirror. Stopping every hour to drink, eat something small, and watch electrolyte levels.

Camp 2 to Camp 3

11,200' – 14,200'

Camp 2 was full of people coming and going. It had a skittles vibe, with bright red, yellow, orange, and green tents sprinkled about. Happy people, disheartened people, but a place where everyone was there for a love for the mountains.

We set up our camp and took in the energy at camp 2. The next morning we set out to retrieve the cache 1500’ below. Skiing the fresh snow was calling to me. Charles went down without his sled, Les took his. Ever the optimist, I opted for ski turns without a sled. The 5 minute ski run was awesome and I was smiling from ear to ear.

I had forgotten my cache was over 50 pounds as part of it had been in my sled. As I put on my pack I sank knee deep in the snow. I struggled with the weight to get back on my skis as the pack had me teetering in every direction in the fresh snow. As we ascended Les was sure to maintain a steady pace to keep the rope fully extended between us so I couldn’t ask to put some of that weight on his sled. What a wise husband. I skinned that 50 pound pack up the hill for 2 hours. Lesson learned, take the sled.

Being at 11,200 feet is really just the beginning of hitting altitude. People can start to show signs of AMS (Altitude Mountain Sickness) and take longer to heal. One party had to stop due a blister that turned into a swollen mass. Another group had been tent bound for 6 days with either Covid or some cold/flu strain.

With the food cache retrieved it was time to look up the mountain yet again. The following day we headed up Motorcycle Hill then on to Squirrel Hill, an off-piste slope that tries to pull the sled off the side of the hill into an abyss, then up to aptly named Windy Corner to cache food at 13,700 feet. This was a strenuous 2,500’ vertical gain day.

Nothing is flat, even if it looks flat it’s going up. The steep hills make the gradual ones appear level but there is never more than 10 feet of even ground. It is exhausting. I would cross step on my left, then on my right, try the duck walk, move to a toe kick rotating as all of my muscles were spent.

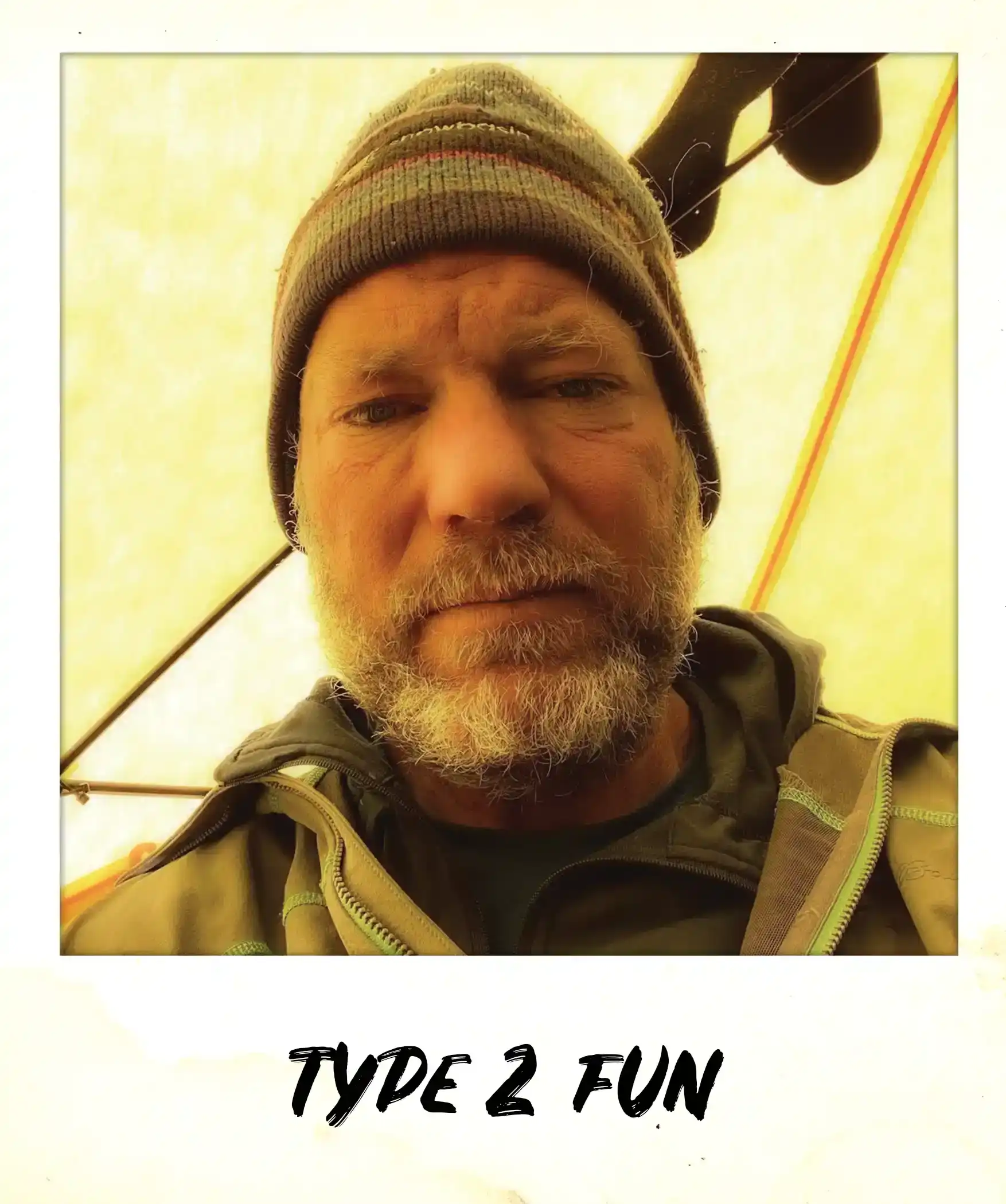

We had left our skis and were using crampons due to the steepness. With exhausted legs we went back down to Camp 2 and melted our water. This daily ritual of melting snow takes 1-2 hours both morning and night. The higher the altitude the slower the stoves become, the thinner the air gets and the colder it is. Aside from a rest day, there isn’t any free time. Melt water, cook food, get dressed, set up camp, take down camp, build walls, sleep, and climb.

The next morning we woke, broke down camp 2 and hauled up to camp 3 at 14,200 feet and what turned out to be a very-long-day.

Camp 3 to Camp 4

14,200' – 17,200'

Camp 3 is at Genet Basin with an imposing headwall on the left and overlooks the Alaska range and world below on the right. It is a tent city with prayer flags and snow walls staking peoples’ claims reminiscent of small-town America. The Forest Rangers are the town mayors in their luxury yurt. Helicopters are coming and going transporting injured climbers off the mountain. This is roughly the altitude of Mount Rainier but feels higher due to the latitude and pack weight. Moving is slow here, night is cold here, but it is such a beautiful place.

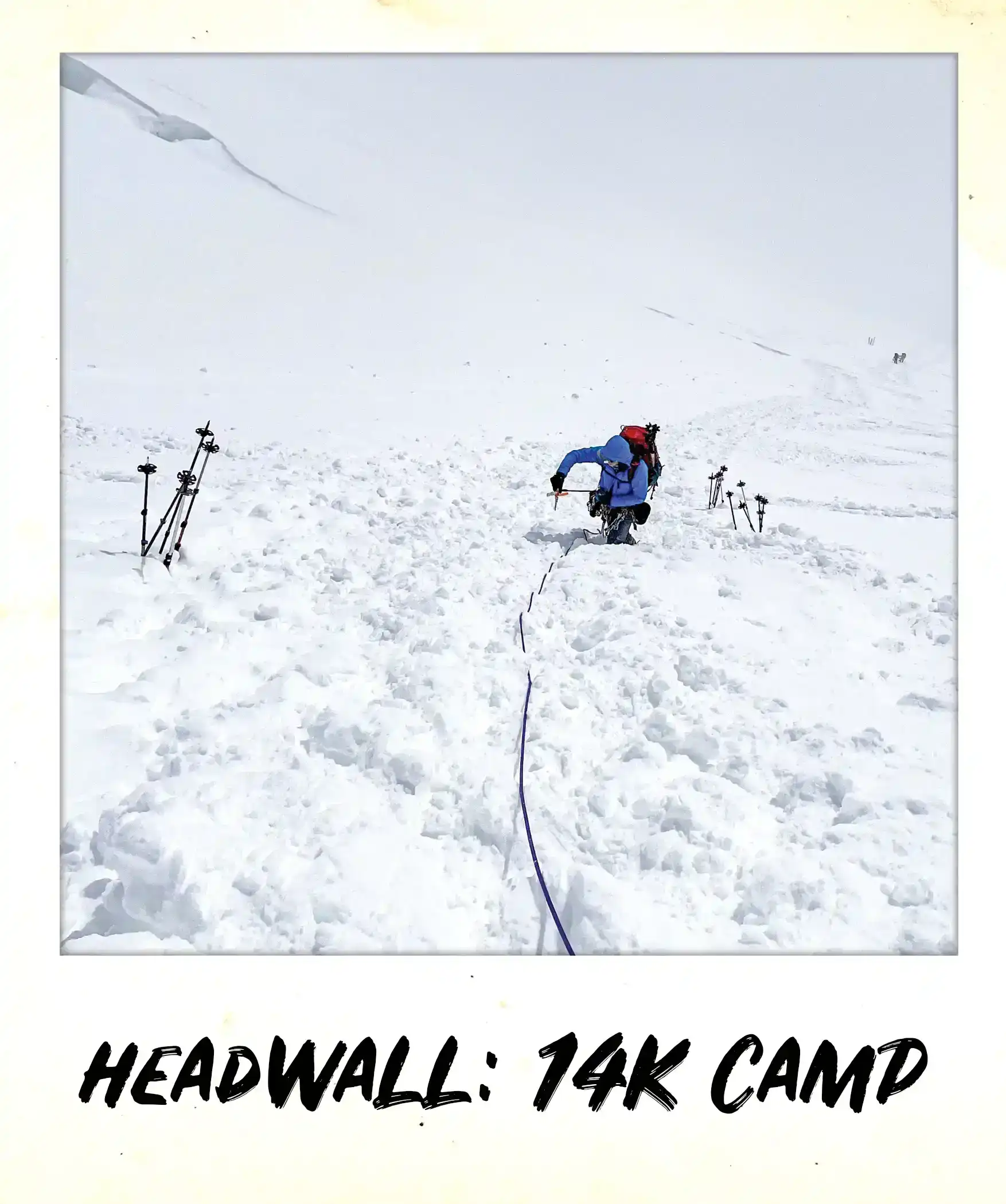

It is getting real now. It was hard up to this point, a kind of routine suffering. From here the headwall leaves out of camp rising up, over a bergschrund (a big crack in the snow similar to a crevasse) and onto fixed lines up the blue ice to the West Buttress.

Climbing the headwall is difficult without a pack but lugging 30 pounds up simply put, sucks. The next day I stayed at camp and built snow walls with a possible impending storm while Charles and Les went back to grab our cache about 750’ below us.

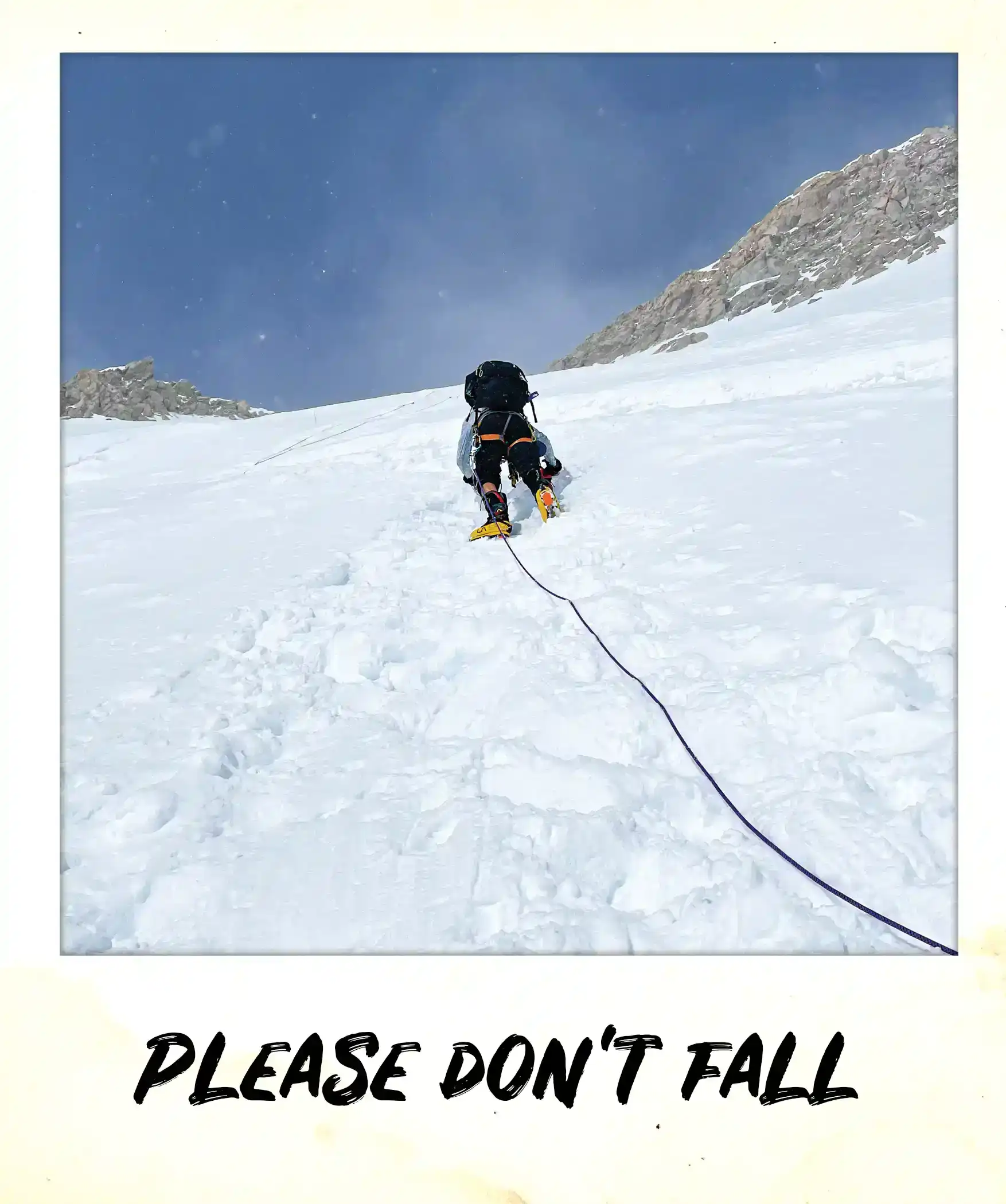

The following day we made our first “run” up the headwall. Once over the gap of the bergschrund we tied into the fixed lines, a series of 12-14 ropes anchored into the ice to catch a falling climber. This was high, airy, hard and freeing. We buried our cache and started back down the descent fixed lines.

I’ve never used an ascender going down and the release device was wonky. The weather changed and that damn ascender kept jamming. Every time I looked down to fix it my breath would freeze instantly on my goggles. We were all freezing. Ultimately I pulled my ascender and used a technique of wrapping my arm around the rope a guide had been using. While not as safe, this method saved me for the rest of the trip. We then sped down, pausing only to change lines. With 4.5 hours up and another couple down we returned exhausted once more.

After a rest day we would be doing it again, but with a much heavier pack. I wasn’t ready to even consider that and just looked forward to a rest day to let my body recover.

More than anything, I realized this was the hardest physical challenge I would ever do and was only half way there. I have climbed Rainier at 14,410’ and Mont Blanc at 15,777’ but this was something very different.

We woke and tore down camp 3 to begin the ascent to camp 4 at 17,200’. As I pulled my pack onto my shoulders the weight was substantial. I don’t complain and I’m sure Les and Charles felt the same, but my eyes began to water 😢 knowing I had over 3000’ to carry this pack that was easily 40 pounds up the headwall and fixed lines again. The kicker was at the top of the headwall I would add all my cache from 2 days prior, about 25-30 pounds. We weren’t coming down to get it this time, we were carrying nearly 70 lbs with us.

I spun around, tied into the rope, and put the additional weight waiting above the headwall out of my mind. The second run up the headwall was easier than the first. At the top, we all grabbed our cache and kept going.

The West Buttress section is stunning but I wasn’t able to appreciate it. The effort to climb and stay safe took all of my focus. The ridge moves left and right, clipping in and out of ropes, steep sections, and precarious boulders to scramble around. Every step matters because if any of us fall we can possibly pull each other down—we are all roped together when moving on the mountain.

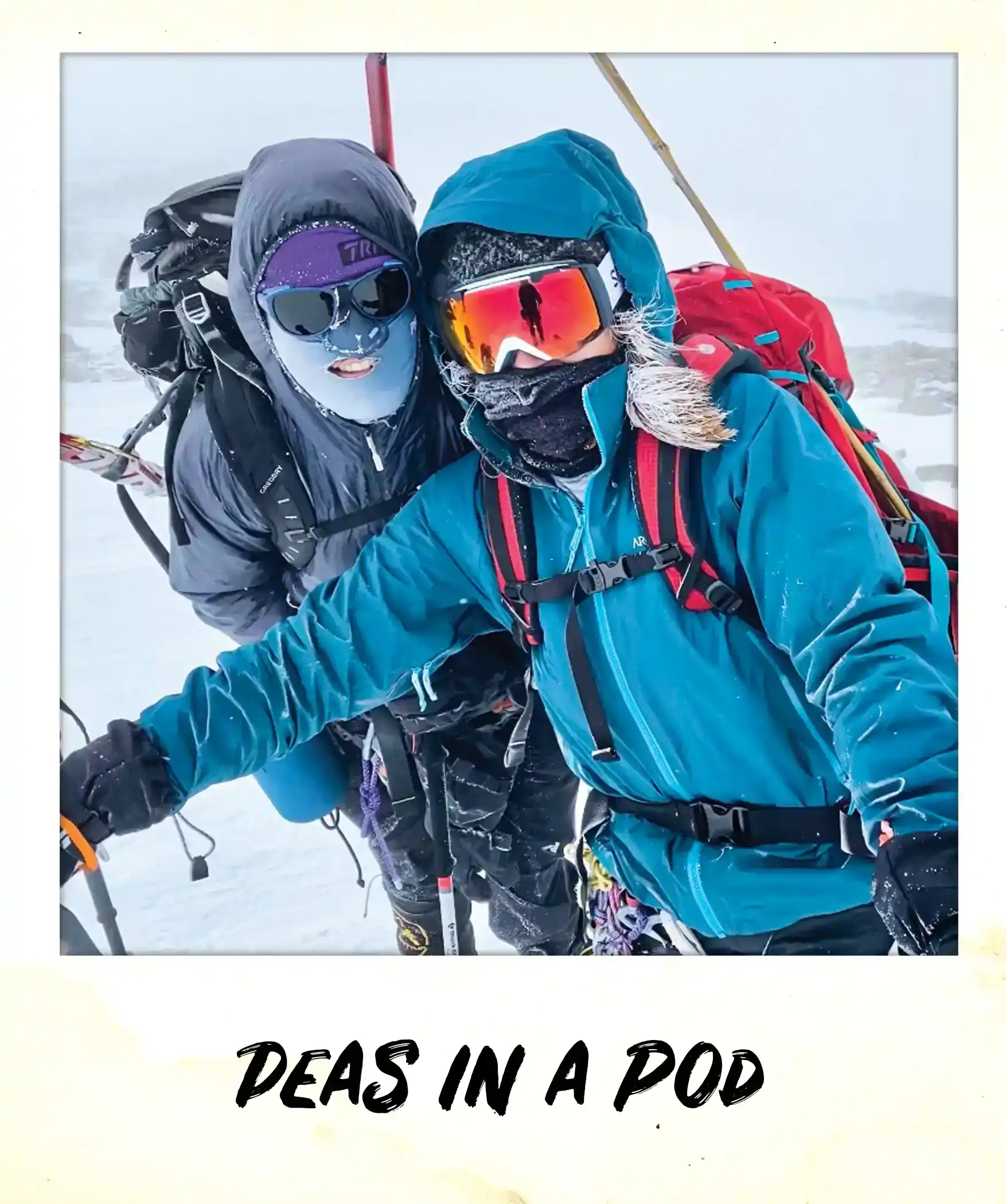

The ascent was long. Passing climbers coming down took time. The ridge was narrow and we’d need to stop and find safe places to pass. Nauseousness set in as we neared camp 4 and I threw up. The beginning of altitude sickness. As we rolled into camp the sun slid behind the mountains and the temperature dropped from 0 to -20. Les and Charles melted snow for water. I was exhausted.

We were all freezing, warming up takes an hour to get into sleeping bags and get heat flowing with your hot water bottles on your feet and belly. We were tired, sunburned, cold and dehydrated. This was only the second time on this trip Denali showed her mild version of freezing temps. Denali can be an inhospitable place.

The following day we would rest before our final climb to the summit. A rest day is like a blur, sleeping for hours, waking only to eat and melt water, maybe read a book. The sounds of helicopters flying in to pick up injured and sick climbers remind you of the seriousness of the situation. I only had one more climb left. Hallelujah.

Summit

17,200' – 20,310’

At 6 pm the Denali Ranger Station broadcasts a forecast for climbers. All of the camp quiets as radios crackle news of impending weather. The summit forecast was clear with -20 temperature and 15-20 mile an hour winds. Storms were moving in over the next few days. However, this was our chance.

Within an hour of waking everything came up that I had eaten. It is hard to eat, drink, and breathe at 17,200 feet. The decision was mine to attempt a summit or rest one more day and risk being forced to weather a storm at high camp. With sunshine on our side, we left camp and began the ascent up the Autobahn, a 1,000’ sloped ramp a Canadian climber had fallen on a few days prior.

As we climbed beyond the Autobahn my pace slowed and chest tightness began on the right side. I slowed down more and it continued to get worse. I told Les and Charles. We agreed to climb the next ridge to the Football Field but by the top, the tension was spreading to the center and further on the right and down. I knew it was time to go down. Right in front of me, 2 hours and about 800’ vertical was the summit. After 2 weeks of suffering it was right there. I could almost touch it from 19,500 feet where I stood.

Les and I turned back. Charles went on to the summit and caught us on the way down to descend the Autobahn safely. As we returned to camp another climber was being flown out with high-altitude cerebral edema. Exhausted, we all crammed into the tent at camp 4. “I’m good with this and I never want to come back,” I recall saying but almost didn’t finish before sleep overtook us all.

As we left Camp 4 the next morning to beat the pending storm, my chest remained strained on any uphill slope. Fortunately, it was pretty much all downhill. The West Buttress Ridge is one of the most stunning places in the world; glaciers, mountains, and sky reach out in every direction. It was even more beautiful because I had climbed it. Our descent was such a paradox to the ascent, almost euphoric with appreciation.

The fixed lines were easy this time and as a slow party descended ahead a skier with a prosthetic leg came up the lines. A total badass soloing up with his ski. Farther down a Warren Miller group with another skier, with a single leg, was climbing up with the film crew. Then in camp, the same female climber I saw at basecamp days ago that had lost her leg in the military was beginning her final descent after summiting a few days prior. My cup was full. This place is amazing. These people inspire me.

After a night back at Camp 3, we broke down camp for the last time. We picked up everything we had brought to this mountain, including the poop buckets, and began our final trip out. With weight back in the sleds it made moving easier until Windy Corner down to Camp 2. The sleds are connected to the backpack but they don’t track behind you, they slide down with the slope of the hill. Our descent was a test of teamwork as the person behind holds back the sled so it doesn’t pull you off the mountain.

As we descended Motorcycle Hill to Camp 2 a 12 year old attempting to climb the highest peaks in all 50 states was heading up. His spirits were high but he wouldn’t go on to summit. We dug out our skis and repacked the sleds as we waited for the sun to set and snow to firm up. We unroped and set out to Basecamp to beat the incoming storm. Moving fast on skis again felt so good, the cold wind on my face but then the sleds started rolling, first Les, then Charles. This was the first time I had belly laughed in 3 weeks. They wanted so badly to actually “ski” but the sleds just wouldn’t relent. I was happy enough to be cruising downhill, turn or no turn, this was heaven.

The mountains were bathed in the sunset as we retraced our climb. At 1 am we arrived back at basecamp. Morning came and our plane showed up just as the storm we were racing began to pour down. As we flew out I was ready to go home, to see my kids, to shower and eat anything that wasn’t dehydrated.

We found the last 2 rooms available in Talkeetna, tucked behind the bar at a restaurant. With old polyester comforters and squeaking twin beds, plaid linoleum floors in dirty yellow; I checked the running water and have never been more thankful for it. After 18 days on the mountain, my armpits looked like small rodents and I stank.

With any luck, I will finish that last 800' in June of 2023 at 50 years young. You can follow my journey on instagram @brandihammon.

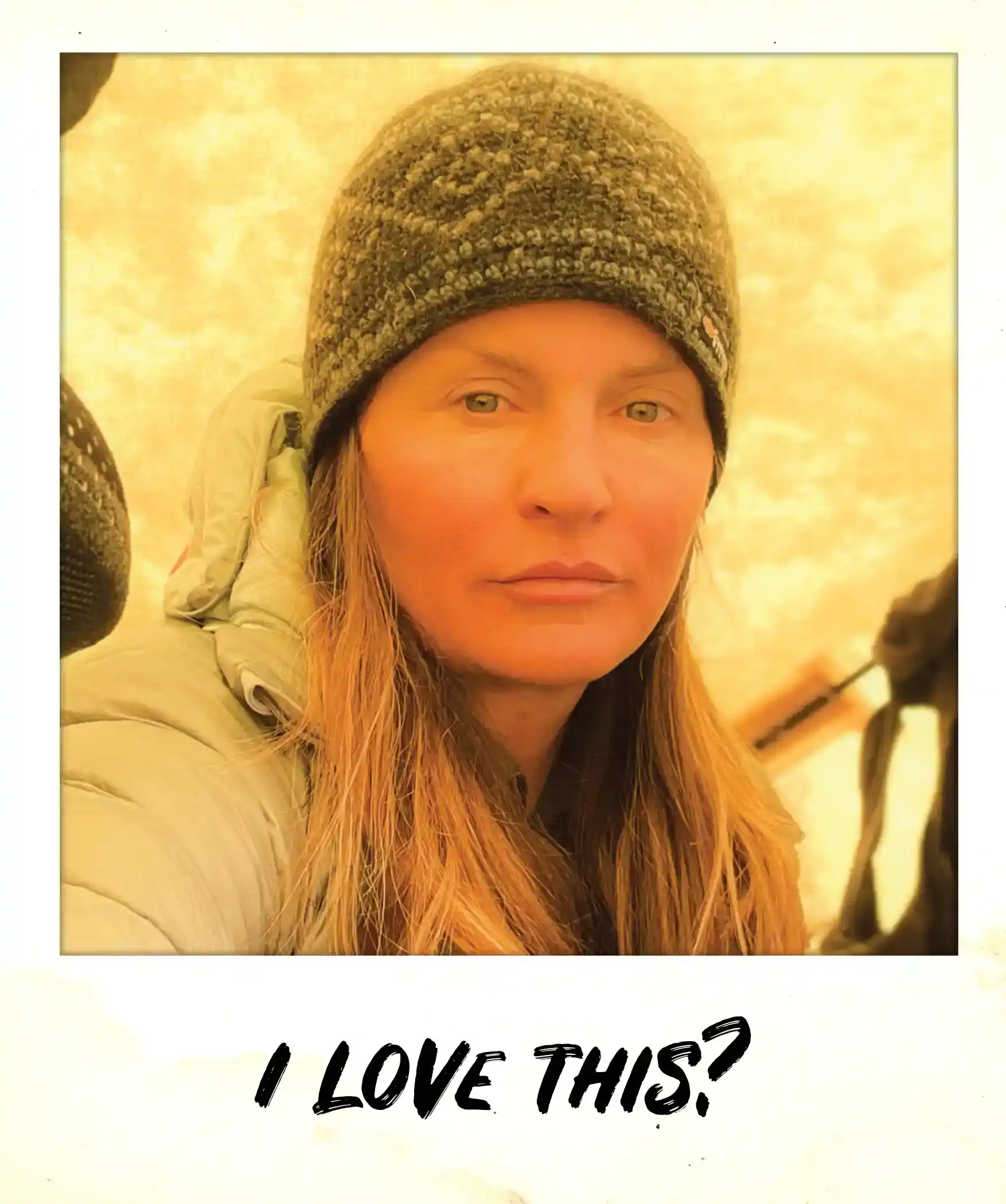

People Ask Why

I think at the core of humans is amazing strength both mentally and physically. An ability to suffer, that in its absence, leaves us capable of appreciating all that is good and beautiful even more. I believe hard things make us stronger. When placed in situations that scare me, where I could actually die, I am fully focused on the task and it clears my brain of all the silly things in life that really don’t matter. The ticker tape of tasks stops and simplicity replaces it; one thought to make the next step solid. After it is all over, it brings forth the things that truly matter with clarity on life, emotions and direction. It parallels my path as an entrepreneur as there are so many hard things to push through, to keep on keepin’ on even when it isn’t fun.

At the end of my life, I want to know I tried and failed, if need be, to chase every wild place and dream I had. And with that, inspire others to do things that scare them just enough whenever possible.

A wise friend once said, “If it scares me, I know it’s the right decision.”

Adventure On

Similar Articles

Categories